Journey

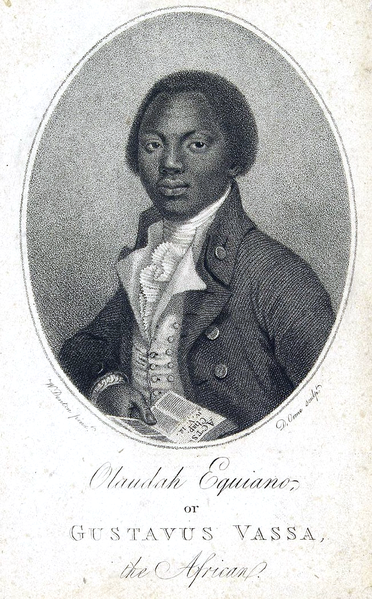

The Abolition Act of 1807 was the result of a twenty-year struggle by antislavery campaigners. Quakers organised the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in 1787, and they enlisted the support of William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Zachary Macaulay and Olaudah Equiano, among others. They faced many pro-slavery defenders.

Merchants who had directly or indirectly invested in the slave trade would lose thousands if an act of abolition were passed. Some Christians also used the Bible to justify slavery, since there were several incidences of slavery in the Old Testament.

Olaudah Equiano (Wikipedia)

Olaudah Equiano (Wikipedia)

There is much debate over why Britain abolished the transatlantic slave trade. Some historians argue that antislavery agitation forced the government’s hand, while others believe it was an exercise in pragmatism, that the slave trade was not as profitable as it had once been. [Jordon, Michael, The Great Abolitionist Sham, (London, 2005), pp.viii-x] It can be argued that the eventual decision to abolish the trade rested with politicians in Parliament. Many historians now speculate that act represented a culmination of a national movement of reform, indicated by the near unanimous vote to pass the act itself. [Walvin, James, Black Ivory – Slavery in the British Empire, (Oxford, 1992), pp.265-287]

After 1807, it was clear that slavery in the British Empire would soon be abolished. Several factors influenced this decision. The number of slave revolts in the Caribbean confirmed to many that slavery was a cruel institution, and many people (ironically) identified with the white religious leaders who were killed in the struggle. Abolitionists stirred antislavery agitation – petitions were signed and presented to Parliament, and there were protests outside Downing Street. Hochschild, Adam, Bury the Chains – The British Struggle to Abolish Slavery, (Basingstoke, 2005), pp.344-66]

In 1832 a new government led by Lord Grey initiated several reform acts, one of which was the gradual abolition of slavery in the British Empire. In 1834, all enslaved individuals under six were freed, but the majority had to complete an apprenticeship for their former master. This period of apprenticeship was exposed as a cruel system, in some cases slavery remained and slave-owners resumed control of their plantations. This ended in 1834. [Walvin, James, Black Ivory – Slavery in the British Empire, (Oxford, 1992), pp.263-5]

The transatlantic slave trade still existed however, and countries like Spain and Portugal made a handsome profit. In response, the Royal Navy launched a squadron to stop slaving ships. Between 1820-70, over 1,600 ships were captured and over 150,000 Africans were returned home, at a cost of £40million to the British government. [Walvin, James, Black Ivory – Slavery in the British Empire, (Oxford, 1992), pp.265-287]

Transatlantic Antislavery

Transatlantic networks between Britain and the United States fostered much anti-slavery communication. The American Anti-Slavery Society appealed to Britain for help, and in 1840 encouraged the organisation of a national campaign against slavery. The Society wanted to pledge:

warfare against the soul-destroying system of slavery, till public sentiment shall become so reformed by the pure principles of Christian love and freedom, that Republic and Christian America, following the example of Great Britain, shall drive slavery from her realms and pledge her moral and political influence for the entire extinction of slavery and the slave trade from the face of the whole earth… the Anti-Slavery cause is a common one…in its success, the whole world is deeply interested and especially England, whose prosperity as a nation will be vastly increased by the extinction of that destructive system, which is cripplying her commerce and manufactures, as well as our own.

In the same year, an International Slavery Convention was held in London. Representatives from American and British societies convened there, but many societies had differing views on the abolition of slavery.

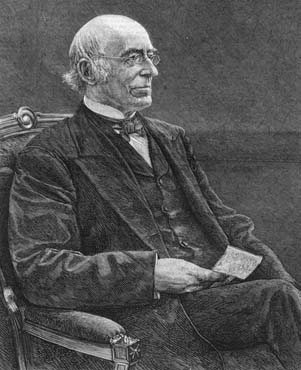

- The American Anti-Slavery Society (or Garrisonians), led by William Lloyd Garrison was based in Massachusetts, and preferred an immediate end to slavery. Garrison owned a newspaper, The Liberator.

- The American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, organised by Arthur and Lewis Tappan, preferred a more gradual approach to abolition, and were distinctly opposed to the Garrisonians.

- Like their American counterparts, the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, founded in 1839 by Joseph Sturge (below), focused on gradual abolition, lobbying Parliament and gathering support for petitions. [Turley, David, The Culture of English Anti-Slavery, (London, 1991), pp.6-103]

Antislavery Convention, 1840 (Wikipedia)

Antislavery Convention, 1840 (Wikipedia)

This was at the height of Douglass’s tour of Britain, and the tensions between the societies were pervasive. Douglass refused to be confined by their disagreement, and spoke at societies favouring immediate and gradual abolition, believing that antislavery was a common cause that all should unite for.However, these divisions between the different societies and the religious convictions of its members often prevented a satisfactory union against slavery. [Stange, Douglas Charles, British Unitarians Against American Slavery 1833-65, (London, 1984), pp.60-1]

Garrison in particular was deemed the focus of radicalism, and was prevented from speaking on a number of occasions during his brief stay in Great Britain in 1846. Despite Frederick Douglass’s presence, anti-slavery remained a “tradition” rather than an activist policy. As a result, some American abolitionists grew disillusioned with the British public, and while certain abolitionists such as Douglass could create fanfare, this had more of a short-term impact on society. [Turley, David, The Culture of English Anti-Slavery, (London, 1991), pp.197-218]

William Lloyd Garrison (Wikipedia)

William Lloyd Garrison (Wikipedia)

In Britain, popular memory attests to the victory of the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade in 1807 and slavery in 1834. The history of slavery is often taken to mean the history of abolition. Antislavery or the slave trade itself did not cease in 1807, 1834 or 1838. In some parts of the Empire, slavery continued to exist, and in others, she took a large percentage of its profits. Over five million were enslaved in India in the 1840s, and it wasn’t until 1928 that an Act of Parliament ended slavery in the Gold Coast of Africa. Merchants and ship manufacturers traded in slave-grown goods and built ships to sell or carry slaves. Furthermore, over 90% of the cotton imported to Liverpool in the early 1840s was slave-grown. By 1849, the Britain was believed to have funded the majority of the slave trade to Brazil and Cuba, and in 1860, slave ships were still being made and equipped in Liverpool. Britain was dependent on the slave trade. [Sherwood, Marika, After Abolition – Britain and the Slave Trade Since 1807, (London, 2007)