Journey

In 1846, Evangelist ministers from the United States and Britain convened in London to form a communion between the two churches. The Evangelical Alliance met in the summer, their meeting lasting for several days. By 1846, Douglass had spent months lecturing across the country and his campaign against the Free Church of Scotland was well known. This had a strong impact on the Evangelical Alliance, as the debate between Christianity and slavery creating a division between those in favour of excommunicating slaveholders and those against it.

I do believe the Evangelical Alliance was hoodwinked, that they were misled; I do not think they really understood the matter…It was these reverend doctors [Americans] who led astray the British ministers in the Evangelical Alliance, on this question of slavery; they dared not go home to America as connected with the Alliance, if anything had been registered against slavery by that Alliance; they knew who were their masters, and that they must be uncompromising…

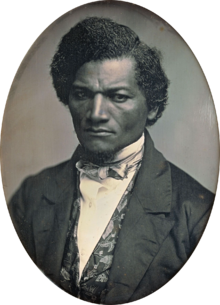

Frederick Douglass (Wikipedia)

Frederick Douglass (Wikipedia)

Some men, like the Reverend J.H Hinton denounced the idea slaveholders should be invited, for the religious community could not afford “to prop and bolster up the system of American slavery.” He rebuked those who thought it pointless to debate slavery, stating, “the Alliance is divided already.” The Reverend Doctor Patton - an American who was outraged at this conversation - declared that the “the price of a slave in Louisiana is always regulated by the price of a pound of cotton at Liverpool.” In other words, slavery was too complicated to make these distinctions, particularly because British ports were dependent on slave-grown cotton.

Eventually, the decision was left to a committee and brushed under the carpet.

Frederick Douglass seized upon this indecision. He did not blame the ministers at the Alliance outright, but used it as an example of how divisive slavery could be. Firstly, he pointed out that the Alliance did not invite Quakers, a religious group who had done much for the abolitionist cause. So why did they invite slaveholders? Secondly, he used the issue to target the American church itself, further exposing and ridiculing the relationship between slavery and Christianity.

The Hampshire Advertiser stated the Evangelical Alliance:

…may be a mere thing of the moment – it may fall to pieces almost as soon as its rickety frame has been erected upon a worthless foundation, and so be soon forgotten – as we are inclined to expect, or, it may be the beginning of some more afflicting form of evil than has yet tormented our church…” (Hampshire Advertiser Saturday 19 September 1846, p.3.)

However, some Britons were outraged at Douglass’s comments. A disgusted reader of the Fife Herald declared:

…although Mr Frederick should be detained a few years longer in bonds, this reflection ought to console him. That his exertions in the cultivation of coffee are vastly more calculated to benefit himself and his country than those nauseous speeches he is in the habit of addressing to those old women of both sexes, who conscientiously believe negro emancipation in our own colonies was the legitimate consequences of their own privations… It is the duty of all the friends of human freedom, ministers as well as others to unite in any well-concerted political movement which has for its object the abolition of slavery but to excommunicate the individual slave-holders would be on their part an act of persecution…

The author also pointed to the irony of Douglass’s “Send Back the Money” speeches. Merchants and plantation owners, those who had made their fortune from slavery in the Caribbean, built the grand buildings of Glasgow and other cities. Should this money be sent back? (Fife Herald, Thursday 14 May, 1846.) This racist attack on Douglass proved his British journey was not always one of harmony that he made it out to be.

While in partnership with other organisations across the world, the British Evangelical Alliance still exists today.