Journey

In 1846, the World Temperance Convention was held in Covent Garden Theatre, London. Committed to the reduction of the sale and use of alcohol, men and religious denominations came from around the globe to participate in the meeting. Temperance was a cause many reformists held dear, and it was particularly important to the followers of Christianity. They believed alcohol spread poverty, violence, and sin and the reduction or even, eradication of drink would create a better society.

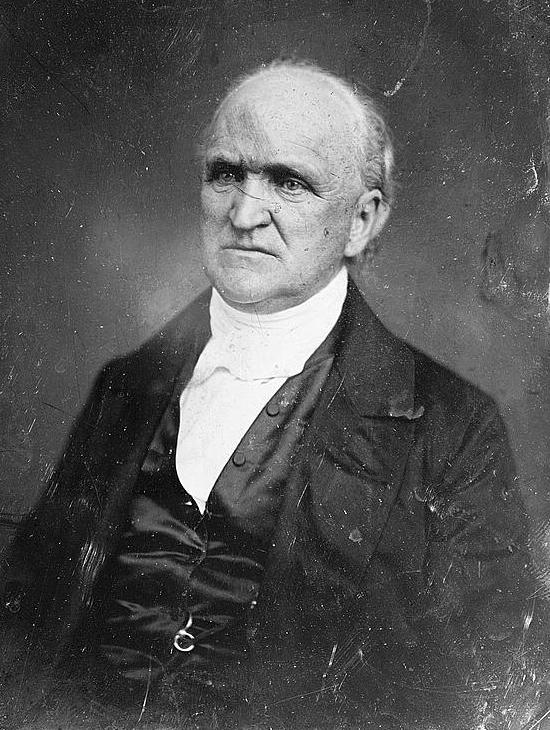

Frederick Douglass strongly believed in temperance, lecturing about its importance throughout his life. He spoke to temperance societies and women’s groups in particular, and believed alcohol endangered the black man’s survival. While in Britain, Douglass occasionally spoke about temperance, and he attended the 1846 World Convention. He was invited to speak on the subject, but not all were content with his speech. Reverend Samuel Cox of Brooklyn, New York (right) started a public exchange with Douglass after the meeting, denouncing his conduct and accusing him of being paid by abolitionists to disrupt the convention. Cox, an antislavery supporter himself, argued that Douglass turned the meeting into a debate about slavery.

Covent Garden Theatre 1827-28 (Wikipedia)

Covent Garden Theatre 1827-28 (Wikipedia)

The moral scene was superb and glorious – when Frederick Douglass, the coloured abolitionist agitator came to the platform…[he] was perfectly indiscriminate in his severities, he talked of the American delegates, and to them, as if he had been our schoolmaster, and we his docile and devoted pupils and launched his revengeful missiles against our country.

Douglass refuted the accusations made by Cox, attesting to the thousands of witnesses at the convention if he was lying. He had urged the convention to accept black people into temperance societies, as well as supporting the cause of antislavery. His reply was published in many abolitionist newspapers.

Sir, you claim to be a Christian, a philanthropist, and an abolitionist. Were you truly entitled to any one of these names, you would have been delighted at seeing one of Africa’s despised children cordially received and warmly welcomed…[this] tells the whole story of your abolitionism and stamps your pretensions to abolition as brazen hypocrisy or self-deception.

More than anything, Douglass’s experience in England alone testifies that slavery remained a controversial issue. It divided the Evangelical Alliance, and compromises had to be made before the meeting could continue. Slavery was disruptive, even in Britain, and visiting Americans at the Temperance Convention or the Alliance could not escape it. These experiences also show that support for antislavery was not united; indeed, those that campaigned for the end of slavery had many ideas over the nature of abolition.

Samuel H. Cox (Wikipedia)

Samuel H. Cox (Wikipedia)