Journey

I, John Brown, am now quite convinced that the crimes of this guilty land can only be washed away with blood.

These were the last words uttered by the radical white abolitionist John Brown. Uncompromising, ruthless and relentless in his divine mission to destroy American slavery, Brown had attempted to inspire a slave insurrection at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia in November 1859. Brown had invited Douglass to join him, but the latter refused – warning Brown his plan was doomed to fail. Douglass was right, and Brown was captured and eventually executed. This assault sent the South reeling, and many states tightened laws and called for stronger punishments towards abolitionists. It was soon discovered that Brown and Douglass had met, and for his own safety, Douglass fled to Canada, and then to Britain, a safe haven once again from unwanted – and perhaps violent – attention.

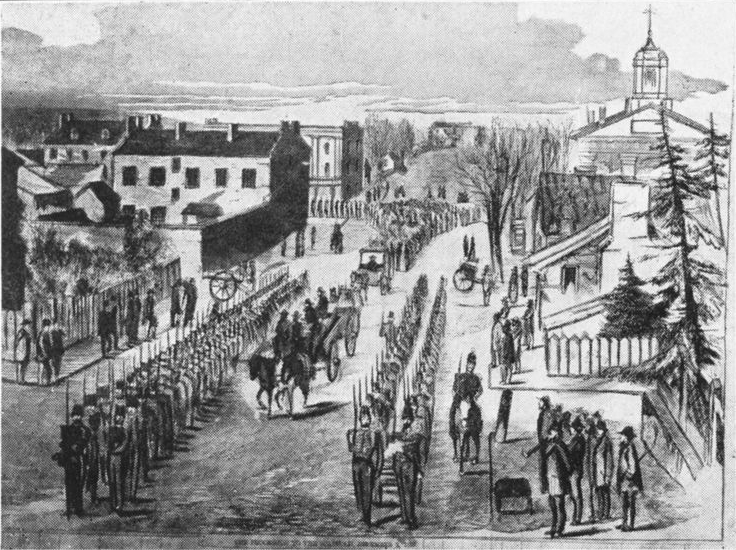

John Brown’s Execution (Wikipedia)

John Brown’s Execution (Wikipedia)

Douglass arrived in the winter of 1859, and immediately visited old abolitionist friends, who organised lectures for him, as they had done in 1845. This time, Douglass did not have much success in British society. Was this because the British public were tired of American slavery? Or had society become more inherently racist? Or was it simply because Douglass failed to create controversy as he had done on his previous visit? Arguably, all of these factors had a part o play, and as a result of this, Douglass remained in the industrial north of England and Scotland, where he had been popular during his previous visit.

While Douglass’s ideology had shifted, his message to the British public was fairly similar, if more urgent. He demanded that the British people use their shared morals, language and identity with Americans to persuade them to destroy American slavery. He was not in Britain to encourage a rebellion, or ask for money or weapons to aid for war. The Leeds Mercury stated:

Mr Douglass proceeded to say that there was a new and strange doctrine in England, he observed since he was here some years ago, he alluded to the doctrine of “non-intervention” as applied to American slavery… All could see that there were times, seasons, conditions and circumstances in which non-intervention was both right and expedient. But he contended that American slavery was entirely without the limits of this doctrine. That vile system of blood was an outrage upon all the great principles of justice, liberty, and humanity, principles which belonged alike to all men of whatever country, colour or clime… in all reason they in England had a right to the expression of an opinion on this subject, and he did not ask them with him to take up arms and go to the Southern states to rescue slaves by force, he did not ask for materials to buy implements of war. All he asked of British men and women was that they would lend him their moral influence and aid for the abolition of slavery.

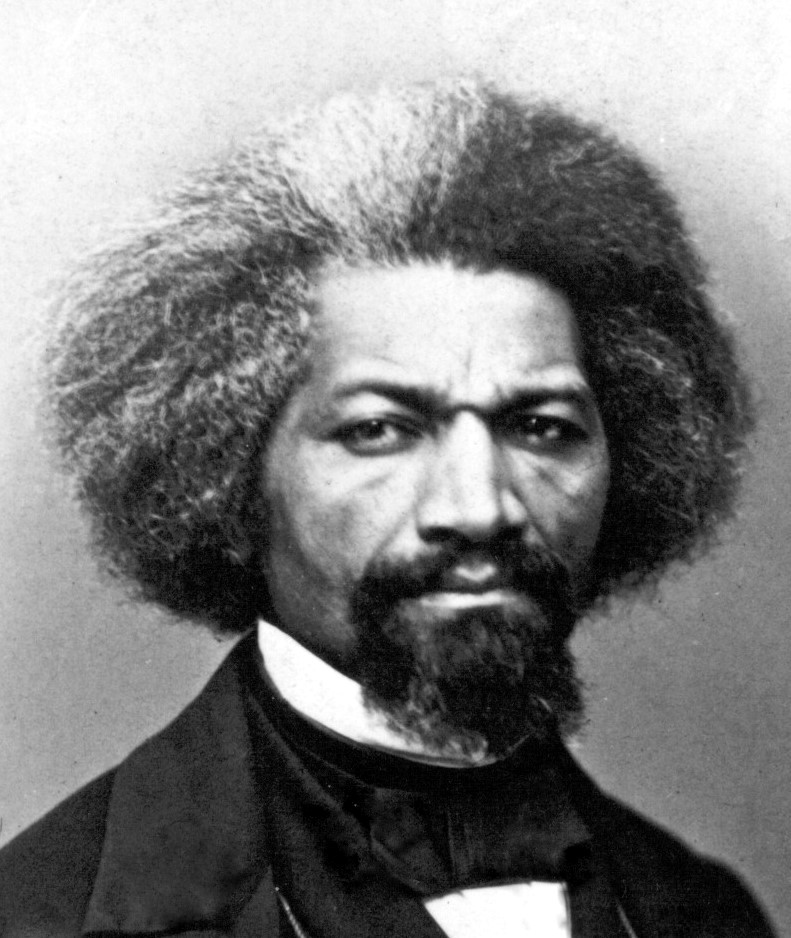

Douglass in the 1860s (Wikipedia)

Douglass in the 1860s (Wikipedia)

Douglass also defended John Brown:

John Brown failed and he failed like a brave and true man and they should see to it that no words of theirs should drop upon his memory to tarnish it… [He] did not go into the slave state for the purpose of shedding blood, that was not his object. He did not go to lift the standard of insurrection, in which lives and property should be sacrificed, but he went with motives as pure as those which took Moses into Egypt to lead out the Israelites…he saw that Captain Brown was charged in a very respectable paper, the Leeds Mercury, as criminally interfering with the laws of Virginia. The Mercury seemed to think that he went into a quiet neighbourhood, peaceful and comfortable and lifted the standard of bloodshed and carnage. It was not so, slavery was itself an insurrection, and the slave leaders were a band of insurgents armed against the rights and liberties of their fellow men.

Douglass returned to the United States in Spring 1860, after the death of his daughter Annie. It would be nearly thirty years before he would visit Great Britain for one final trip.

1880s

Years after the Civil War, Frederick Douglass was not forgotten in the British press. Newspapers reported on his political appointments, such as his position as Minister to Haiti, and other Northern newspapers in Scotland and Manchester published anecdotes, stories and even jokes made by Douglass, often just two or three lines long. In most cases, he was described as the “famed coloured orator” or the “negro anti-slavery advocate” and in other papers there is no description at all - for some, this man did not need an introduction.

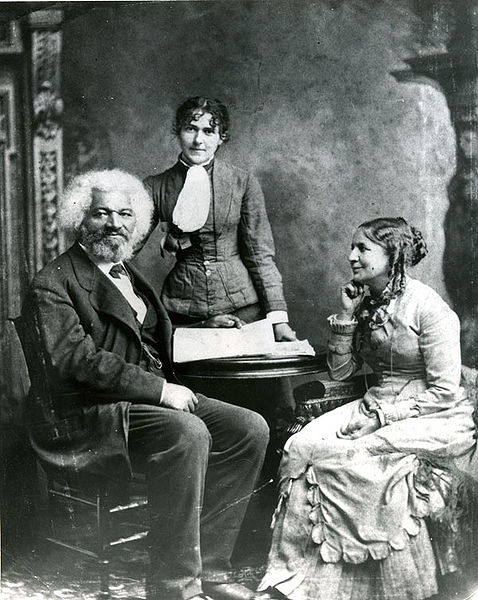

After Douglass’ second marriage to Helen Pitts, the couple decided to travel around Europe between 1886-7. Douglass had not visited Britain since before the Civil War, and it was a chance to meet with the families and friends he had corresponded with for many years.

Douglass, Helen Pitts and Helen’s sister (standing) (Wikipedia)

Douglass, Helen Pitts and Helen’s sister (standing) (Wikipedia)

Although he did speak at some social reform meetings, Douglass did not visit Britain to lecture or gather support as he had done in 1845 and 1859. When he did lecture, he spoke of the problems still facing African Americans: although the Civil War had brought abolition, black men and women had not won true freedom.

Mr Douglass told his hearers that 41 years ago he had visited England as a fugitive slave, and his free papers were purchased by ladies in this country; in 1859, he came as an exile, to escape the pro-slavery fury after John Brown’s attack on Harper’s Ferry; now he came as an American citizen, who had received the recognition of the American Government. Speaking of the present condition of his people, he regarded it as hopeful, considering the circumstances of emancipation. No provision was made for them in the War which set them free; they were left landless and destitute – not as in Russia, where the emancipated serfs had been given land; and their old masters were naturally hostile to them, as the witnesses to their humiliation. They have, however, rapidly increased in numbers, they are acquiring education and property, and their social position is improving, in spite of many serious obstacles.

A recurrent theme in his speeches and writings during this trip was racism was still rife in the United States, something that the Civil War or time had not yet eradicated.