Abolitionists

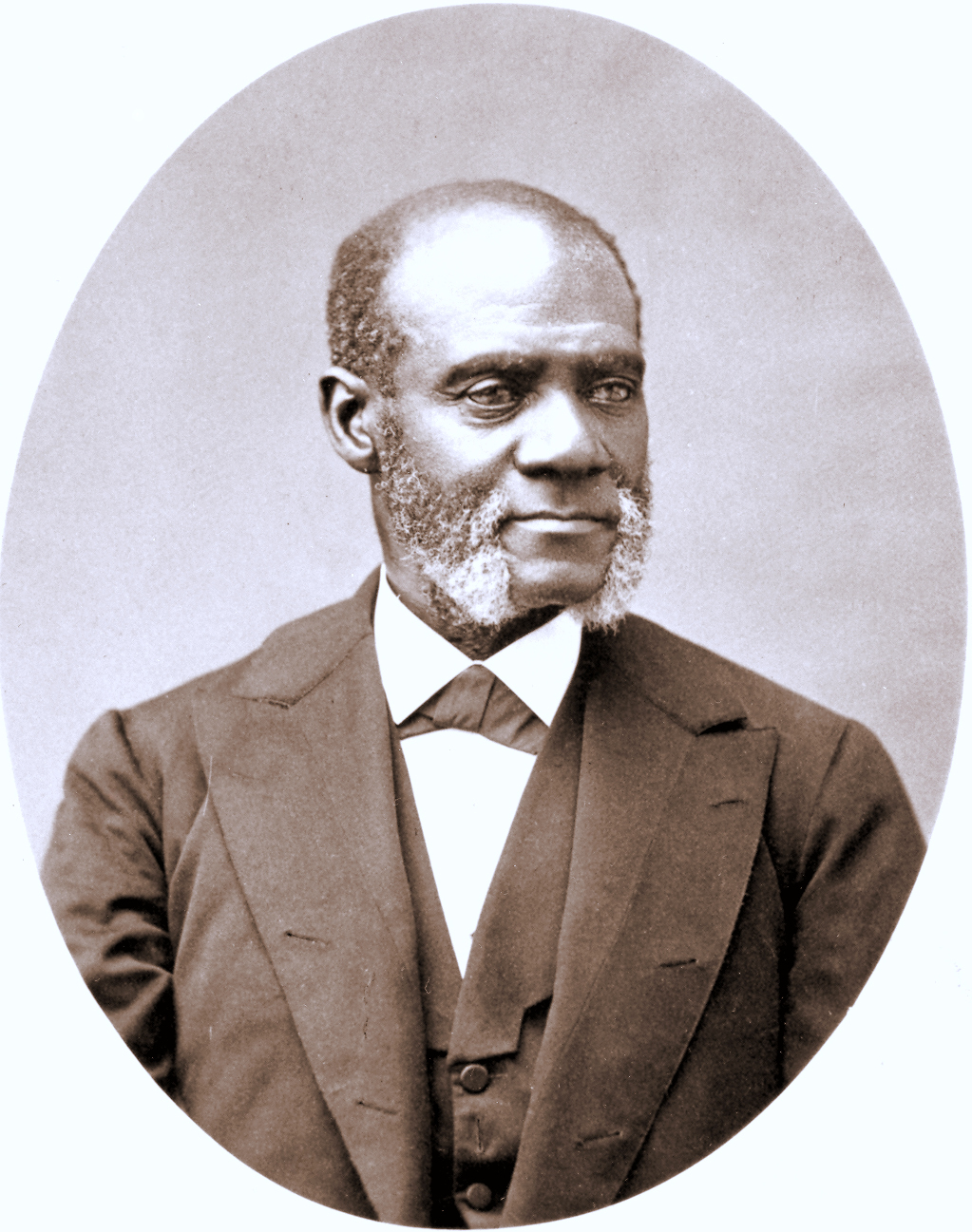

In 1851 in Belfast, the radical preacher and abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet declared that the US “was staggering under the putrid corpse of American slavery.” A fiery orator, Garnet was disgusted at the racial injustice that infected the nation, together with the violent white supremacy which underpinned the peculiar institution.

Born into enslavement in 1815 in Maryland, Garnet escaped with his family while still a young child and grew up in New York to become an ardent and passionate antislavery orator. He trained as a pastor and infused his abolitionist speeches with religious imagery and militancy. He worked with William Lloyd Garrison, but clashed with him over the concept of arming enslaved women and men: in 1843, Garnet strongly advocated for such a rebellion, which was one factor in leading to their separation as friends. Garnet joined the Liberty Party and supported black emigration outside of the US to Liberia and the West Indies.

In 1850, he travelled around the British Isles advocating for the Free Produce Movement in connection with English abolitionists like the Richardson family. Garnet also raised money to redeem the Weims family from slavery.

After his trip to Britain, Garnet and his wife Julia lived in Jamaica and Washington D.C. During the Civil War, he raised support for African American troops in the Union army.

Garnet died in 1882 in Liberia.

The domestic ties that bound England to America were so numerous that he believed he had never addressed a British audience that was without, in a greater or lesser degree, some dear friend in America. Denouncing the atrocities of slavery as directly antagonistic to a pure and holy religion, and believing that he who “soweth the wind shall reap the whirlwind,” he asked his audience to picture themselves the fearful effects of a day of retribution, in which every institution in that vast continent should be shaken to its centre, and their own friends and relatives involved in ruin. The celebrated Thomas Jefferson, himself a slaveholder, contemplating the day when three millions of slaves might take a fearful retribution upon their oppressors, said, “I tremble for my country.” (Hear, hear.) Again, if he supposed that the time would come when America should be what she now professed to be – when common-sense, humanity, reason should have triumphed – when the dark cloud of slavery should have rolled away – when Africa should have received her rights, and justice should have been meted out to her long-oppressed sons – when, in short, America should become that which it is not at the present time, the land of liberty – would not the English people, as friends of progress, of civil government, of humanity, be interested in so vast a change?