Abolitionists

Charles L. Remond’s visit to Britain in the 1830s set the precedent for other visiting African Americans throughout the century. He won great support in Ireland and used his powerful oratory to convince Britons of the brutality of American slavery.

He said he had no other apology to offer for his attendance there than the single fact that he stood upon that soil upon which the slave had but to tread and he became free – that he breathed, for the first time, that atmosphere which the bondsman had only to inhale and his fetters dropped from his limbs.

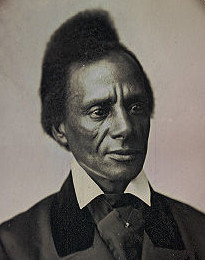

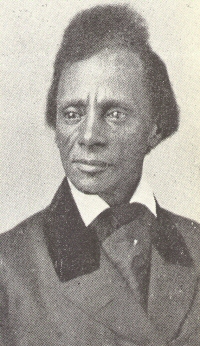

Born free in 1810, Remond was the brother of Sarah Parker Remond. In his 20s, he began speaking against slavery for William Lloyd Garrison’s organisation, the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society and both men travelled to London for the World’s Antislavery Convention in 1840.

Charles Remond (Wikipedia)

Charles Remond (Wikipedia)

Remond lectured on slavery in both America and in Britain, attracting much interest and support in both countries. During the Civil War, Remond urged fellow black men to serve in the United States Colored Troops for the Union Army.

He died in Boston in 1873.

There was not on that soil a single free man of colour, as the term was understood here. That unhappy race were liable to punishment and outrage, not because they had committed crime, but because they were Africans. No inquiry was made whether a man of colour was destitute of character – his colour, or rather his blood, subjected him to all the horrors of the yoke. And if the individual before them were thrown into prison, and after a few months released, after having received a few stripes, or kicks, or cuffs to whom could he look for redress?