Journey

In August 1845, Frederick Douglass set sail for Liverpool, England on a ship called the Cambria. Before his trip had even begun, he was met with pro-slavery defendants who argued against his passage.

In a letter to William Lloyd Garrison in September 1845, he wrote:

From the moment we first lost sight of the American shore, till we landed at Liverpool, our gallant steamship was the theatre of an almost constant discussion of the subject of slavery commencing cool but growing hotter every moment as it advanced…the truth was being told and having its legitimate effect on the ears of those who heard it…the slave-holders, convinced that reason, morality, common honesty, humanity and Christianity, well all against them, and that argument was no longer any means of defence…[so] they actually got up a mob – a real, American, republican, democratic, Christian mob and that too, on the deck of a British steamer…

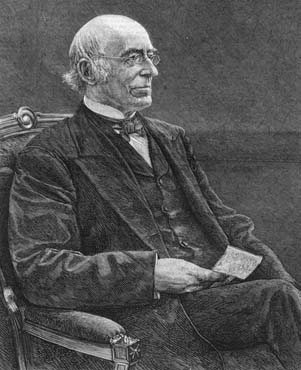

William Lloyd Garrison (Wikipedia)

William Lloyd Garrison (Wikipedia)

The pro-slavery supporters demanded he should return to his berth, and several decried he should be sent back to slavery. Some even threatened to throw him into the ocean, but:

…a noble-spirited Irish gentleman assured the man who proposed to throw me overboard that two could play at that game, and that, in the end, be thrown overboard himself. The clamor went on, waxing hotter and hotter, til it was quite impossible for me to proceed…

Douglass described the experience in more detail in a letter to Thurlow Weed, a fellow abolitionist, in December 1845:

It is clear that slavery in our country can only be abolished by creating a public opinion favorable to its abolition, and this can only be done by enlightening the public mind – by exposing the character of slavery and enforcing the great principles of Justice and Humanity against it. To do this with what ability I may possess, is plainly my duty…Not being able to defend their “peculiar institution” with words, [the slaveholders] meanly – and I may add foolishly – resort to blows, vainly thinking thus to cover up their infamy. When will they learn that all such attempts only defeat the end which they are intended to promote, as it only calls attention to an institution which can pass without condemnation, only as it passes without observation. The selfishness of the slaveholder and the horrible practices of slavery must ever excite in the true heart the deepest indignation and most absolute disgust…”

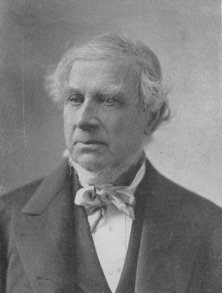

Thurlow Weed (Wikipedia)

Thurlow Weed (Wikipedia)

During his tour of Britain, Douglass spoke about this treatment on a number of occasions. He wanted to embarrass America – pro-slavery advocates were aggressive and violent in their defence of slavery, and he compared this experience with the favourable treatment he had received thus far in England. Slavery (and racism) were persistent problems that needed to be abolished. One thing was certain, however: from the moment Frederick Douglass stepped foot on British soil, no slaveholder was safe from his vitriolic attacks.