Journey

When the American Civil War began in 1861, few would have believed it would last nearly five bloody and divisive years. By this time, Frederick Douglass was one of the most famous abolitionists, but the conflict thrust him into the spotlight. In a war that was caused by slavery, Douglass became a representative of the millions of enslaved individuals still in bondage, and his fiery speeches demanded that slavery should be abolished.

Douglass was also a fierce advocate argued for the enlistment of African American soldiers and their equal treatment (including pay) with white men. He visited the White House and discussed such matters with President Lincoln. In Britain, newspapers reported almost daily on the battles and political developments, and Douglass’s speeches were printed almost verbatim across the country.

President Lincoln’s 2nd Inaugural - see if you can spot Douglass! (Hint: he’s near the wall) (Wikipedia)

President Lincoln’s 2nd Inaugural - see if you can spot Douglass! (Hint: he’s near the wall) (Wikipedia)

For example, in 1862, Douglass wrote “THE SLAVE’S APPEAL TO GREAT BRITAIN” which was distributed through the leading national and regional newspapers. It was a powerful address, designed to invoke the British patriotism - Britain had abolished slavery in the Empire and she had a duty to stand by her decision and help destroy the traffic the world over:

You are now more than ever urged, both within and from without your borders, to recognise the independence of the so-called Confederate States of America. I beseech and implore you, resist this urgency. You have nobly resisted it thus long…Oh! I pray you, by all your highest and holiest memories, blast not the budding hopes of these millions by lending your countenance and extending your honoured and potent hand to the blood stained fingers of the impious slaveholding Confederate States of America. For the honour of the British name, which has hitherto only carried light and joy to the slave and rebuke and dismay to the slaveholder, do not in this great emergency be persuaded to abandon and contradict that policy of justice and mercy to the negro which has made your character and your name illustrious throughout the civilised world…Their pretended government is but a foul, haggard and blighting conspiracy against the sacred rights of mankind, and does not deserve the name of government. Its foundation is laid in the impudent and heaven-insulting dogma that man may rightfully hold property in man and flog him to toil like a beast of burden. Have no fellowship I pray you, with these merciless menstealers but rather with whips of scorpions scourge them beyond the beneficient range of national brotherhood.

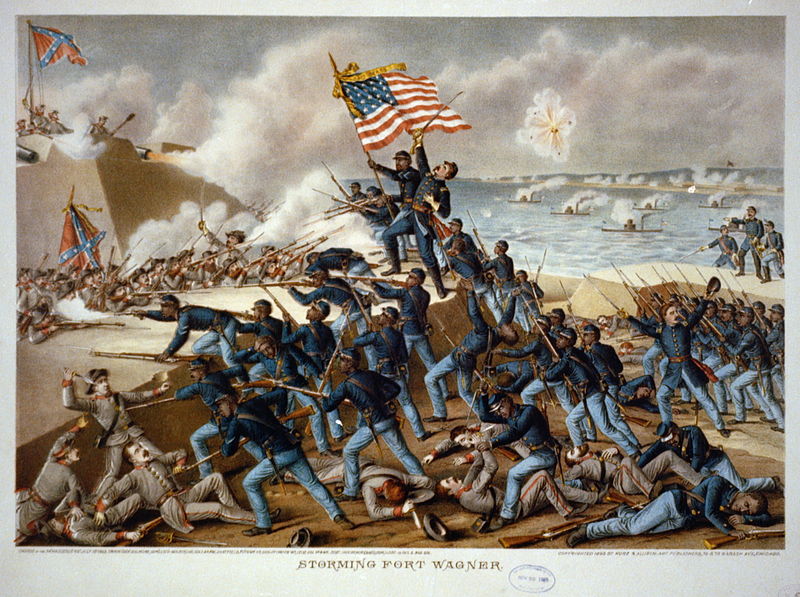

54th Massachusetts Storming Fort Wagner, painted in 1890 (Wikipedia)

54th Massachusetts Storming Fort Wagner, painted in 1890 (Wikipedia)

Douglass urged black men to fight in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment and championed their service throughout the war. He also constantly wrote to abolitionist friends in Britain throughout the 1860s, updating the British on the Union’s progress. Many of his friends had strong connections to local newspapers and his letters were printed in the press concerning his views on President Lincoln, slavery and the war in general. In the letter below, he refers to the “prospects of the negro in America.”

I never was listened to with such attention as now. My leading idea now before the people is, “no war but an abolition war, no peace but an abolition peace.” The government and people still need line upon line and precept upon precept. At Washington, a few evenings ago, where I went to deliver two lectures in aid of the contrabands or freedmen, and where I raised more than $100 for them, the house was densely packed by white and coloured people, and the papers say that 2000 went away unable to gain admission. Now think of me in Washington, where three years ago, I should have been murdered in ten minutes had I dared to open my mouth to my enslaved people