Journey

Douglass’ British trip influenced him for the rest of his life. Perhaps the most important experience for Douglass was the purchase of his freedom by his British friends. Ellen and Anna Richardson had written to Douglass’ former master, Hugh Auld, demanding a price for his freedom. They agreed on £150; the money was raised and sent to Auld. Thus, when he returned to the United States, Douglass would be free.

This generous act however did not please all abolitionists. For example, Henry C. Wright bemoaned the purchase, arguing that it justified the system of slavery by acknowledging Douglass as property:

That certificate of your freedom, that ‘Bill of Sale’, of your body and soul, from that villain, Auld, who dared to claim you as a chattel, and to set a price for you as such…you will sink in your own estimation if you accept that detestable certificate of your freedom; that blasphemous forgery, that accursed Bill of Sale of your body and soul…I would see you free – you are free, you always were free, and the man is a villain who claims you as a slave, and should be treated as such.

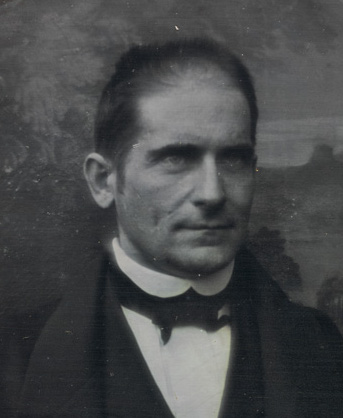

Henry C. Wright (Wikipedia)

Henry C. Wright (Wikipedia)

It was not just Henry Wright that objected to the ‘purchase’. British abolitionist, Mary Welsh, concurred: “Some of us have been very much grieved at Emma Richardson getting that money collected to purchase Frederick Douglass’s [freedom]. We feel it a compromise of principles in thus recognising the right the slaveholder had to sell him and many of us who are the warmest friends the cause has, both here and in Glasgow acknowledge no part in it, from real principle, it has grieved us exceedingly. However, we are now collecting a little for Frederick himself into which we can heartily enter…”[Mary Welsh to Maria Chapman, 1846, Edinburgh, Boston Public Library Anti-Slavery Collection, 1-6, http://archive.org/details/lettertomydearmr00wels6]

Douglass replied to his critics:

I am legally the property of Thomas Auld, and if I go to the United States, Thomas Auld, aided by the American government can seize, bind and fetter, and drag me from my family, feed his cruel revenge upon me, and doom me to unending slavery…it was not to compensate the slave-holder, but to release me from his power; not to establish my natural right to freedom, but to release me from all legal liabilities, to slavery.

In a farewell speech in London, Douglass thanked the British public for their hospitality in the nineteenth months of his trip. He stated that for the first time, he knew what it was to be free, and he would return to the United States as “a human being.” In Britain, Douglass could move freely without restriction, dining with upper class gentlemen and visiting the Houses of Parliament. In his speeches, Douglass would frequently allude to this contrast to the United States in a demonstration of what Alan Rice calls strategic anglophilia: by painting Britain as a land of freedom, he attempted to shame Americans into recognizing the sin of slavery.

Some historians have named Douglass a “triumphant exile”. He became a more confident speaker, and the lack of racism he encountered in Britain (compared to the United States) convinced him the abolition of slavery and discrimination was possible. For a brief period, Douglass considered moving to England permanently, encouraged by many of his British friends. He decided against it however, as he wished to campaign for abolition in his own country and do what he could for his fellow brethren. [Rice and Crawford, ‘Triumphant Exile – Frederick Douglass in Britain 1845-7, from Rice and Crawford (eds) Liberating Sojourn – Frederick Douglass and Transatlantic Reform, (Georgia, 1999), pp.2-9]

Because of his tour abroad, many people in the United States, not necessarily abolitionists or proslavery advocates, knew his name. His sojourn made him increasingly popular among abolitionist circles, and he lectured on antislavery for nearly twenty years until the Civil War. Not all Americans welcomed him home however. Slaveholders despised him and his abolitionism, and others disliked the idea he had shamed America to a British audience. The United States was a nation to be respected, and its liberty or its philosophy should not be mocked from abroad. Regardless, this was the beginning of Douglass’s impact on American politics and society.

Reflecting on his British travels in his autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, (1855), Douglass acknowledged that some of his campaigns failed, notably against the Free Church. While the money was not returned, he argued “we were amply justified by the good which really did result from our labors”, something which may be applied to his British sojourn. More importantly, the trip heavily influenced him and he returned to the United States a new man.

The North Star

On his return to the United States, fuelled by the independence and support he had received, Frederick decided to set up his own newspaper, The North Star. British friends raised money for this enterprise, to which he gratefully acknowledged on numerous occasions. This was not welcomed by everybody, and many of the Garrisonian abolitionists in America and in Britain believed it to be an inevitable failure. In the first edition, Frederick explained its goals, making it clear that he would pursue his newspaper, despite the critics:

It is neither a reflection on the fidelity, nor a disparagement of the ability of our friends and fellow-laborers, to assert what “common sense affirms and only folly denies,” that the man who has suffered the wrong is the man to demand redress,—that the man STRUCK is the man to CRY OUT—and that he who has endured the cruel pangs of Slavery is the man to advocate Liberty. It is evident we must be our own representatives and advocates, not exclusively, but peculiarly—not distinct from, but in connection with our white friends. In the grand struggle for liberty and equality now waging, it is meet, right and essential that there should arise in our ranks authors and editors, as well as orators, for it is in these capacities that the most permanent good can be rendered to our cause.

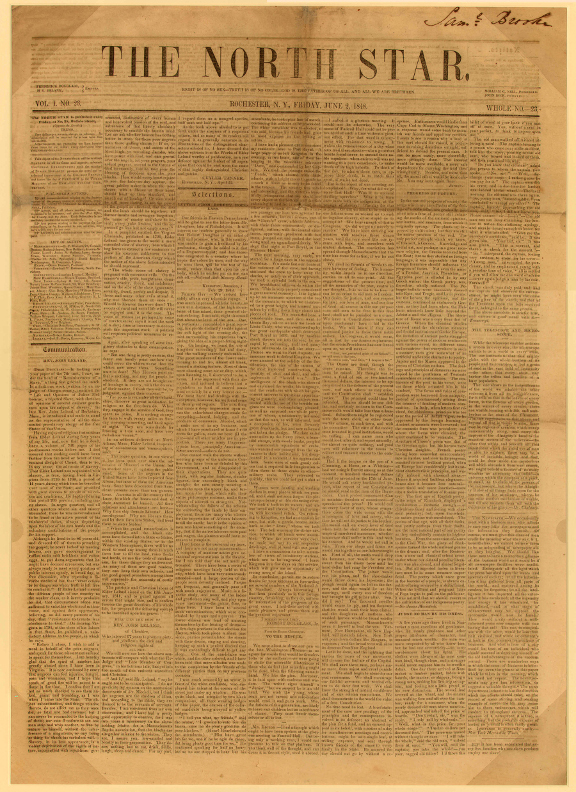

The North Star Newspaper (Wikipedia)

The North Star Newspaper (Wikipedia)

These objections were made very clear by the Garrisonian abolitionists:

It was a knowledge of facts like these, that led us carefully to weigh the proposition for establishing a newspaper, at the present time, by Frederick Douglass, and that brought us to the conclusion that it would be wise in him to defer the risk and the drudgery of such a task, and to give himself unreservedly to the great and successful work of addressing the multitudes who are everywhere eager to hear his eloquent and triumphant appeals…of one thing, we and his friends are certain, as a lecturer, his power over a public assembly is very great, and it is manifestly his gift to address the people en masse. With such powers or oratory, and so few lecturers in the field where so many are needed, it seems to us as clear as the noon-day sun that it would be no gain, but rather a loss to the antislavery cause to have him withdrawn to any considerable extent from the work of popular agitation, by assuming the cares, drudgery and perplexities of a publishing life.

This proved to be another bone of contention between Douglass and the Garrisonians, and was one of the factors that led to their separation in the early 1850s.